In the News

Life of a Depot

By Joy Summar

From the Columbia Daily Herald June 2001 also published in “Historic Maury”

All my life I can remember driving down Depot Street in Columbia, Tennessee and seeing a large stone building standing vacant with weeds growing rampant around the building. Some looked as if they were growing in and out of the building. Windows were broken. The air around it seemed to hang heavy with depression and desolation. As I grew older, I learned that it had been the old train station, but I did not know much more than that. When had it been built? Why was it not in use anymore? What did it look like inside? Does it have a future other than sitting as an empty reminder of my town’s past? What did this building have to tell me?

On November 13, 1903, the depot was opened after almost a year and half of planning.

It is now easier to determine the depot’s past than its future. On November 13, 1903, the depot was opened after almost a year and half of planning. In February 1902, two Columbia businessmen, Major W. J. Whitthorne and Mr. John P. McGaw Jr., decided it was time for a new, better depot. They persuaded the Louisville and Nashville Line to help with the building of the new depot by securing options on property adjacent to the new depot site, and new streets that would be needed for access to the depot.

In April of the same year “the Board of Mayor and Aldermen with one dissenting vote passed the new depot proposition to give to the L & N Railway Co. fifteen or twenty thousand dollars of the people’s money towards building a new depot for the convenience, comfort, and accommodation of the railroad’s customers.” In the proposition, L & N was responsible for building the depot “with arrangement sufficient to provide ample accommodations for the passenger business at said station for many years to come. ” The railroad company was also responsible for building the new roads and underpasses needed for the station, for damages occurring to the surrounding property, and for half of the amount needed to purchase the land for the depot. The city was responsible for building the sewer system to the depot and providing the other half of the payment for the needed land.

There was some local opposition to the depot proposition. The funding for the project apparently created some contention within the Board of Mayor and Aldermen, although in the end only Alderman Bennet voted against the project. The people required to sell their property were not content with the amount of money offered to them, and the Columbia Herald was opposed to the plan, calling it “looting of the public treasury”. The editors evidently believed that the railroad company should pay for the entire undertaking, but indicated that they would not continue the discussion unless Alderman Bennett or someone else wanted to voice their opinion on the subject. The Columbia Herald did bring to public notice a few aspects of the plan that might in some way be harmful to the public as they traveled through the area, and said that the railroad company could be forced under law to build a new depot.

The paper’s objections notwithstanding, the final reading of the depot proposition was passed on May 16, 1902 with Alderman Bennett still dissenting. The Board also passed a series of ordinances which directed funds to be set aside to purchase the needed land located near the railroad, and which authorized the closing of parts of several roads and the construction of a new road and underpass.

Later another local businessman, J. L. Hutton, came forward and offered to buy the necessary property and carry out the city’s part of the deal, as long as he would not be held liable for damages that might occur. All he asked for was the $10,000 the city was borrowing from the railroad. He proposed to change the location of the street being built, and allow for warehouses to be built along the tracks. He made this proposition with the approval of L & N, and the Board accepted his offer and conditions.

By June 27th Hutton had secured the deeds to the land required, and work was ready to begin. President Milton Smith of L & N announced that the company was willing to spend $200,000 on the site. This would include construction of the passenger depot, a roundhouse, and machine yard. These facilities were needed because Columbia was centrally located on the Nashville-Decatur line, and also because the offices of the superintendent of the railroad and road master were being moved from Nashville to Columbia.

On November 13, 1903, the Union Station was officially opened, with the Superintendent of the line and the rector of the Episcopal Church, Reverend Quinn, speaking. The first train left the new depot, heading to Mt. Pleasant, at one o’clock. In the years that followed, many notable people passed through the depot, among them President William Howard Taft, General John Pershing, entertainer Buffalo Bill, evangelist Billy Sunday, and attorney William Jennings Bryan. But the real importance of the new depot was the part it played in the economy of the area.

…the real importance of the new depot was the part it played in the economy of the area.

Throughout its early years, the depot was the heart of transportation and freight shipping for Columbia and the surrounding county. Local agricultural products, such as corn, wheat, cotton and livestock depended on the depot shipment. The mail service and the Railway Express Agency, which operated out of the depot, were both important side enterprises of the railroad. Since the middle of the 19th century, Columbia had been an important point in the development of the railway system. In 1852, charters were obtained for the Central Southern Railroad and the Tennessee and Alabama Road, with the Maury County government voting to take $140,000 and $200,000 respectively in stock. The Central Southern Line built a railroad from Nashville to Columbia, and the Tennessee and Alabama line continued to the Alabama state border. The Tennessee and Alabama Central Railroad was added later to help complete the line. The first train steamed through on June 16, 1859, with the whole town turning out for a barbecue to celebrate the momentous event. Each line operated as separate companies through the Civil War. After the war, in 1866, they joined to form the Nashville and Decatur Railroad. Later the Nashville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis Railroad built a line to Dercherd in order to connect with its main line. In 1871, the Nashville and Decatur Railroad was leased by the Louisville and Nashville System. L & N continued to operate the line, and later gained a controlling interest in the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis line. In 1982, L & N was purchased by Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Company, which is now a division of CSX Corporation.

As the use of the railroads for freight and passengers increased in the 19th century, depots were needed as places for passengers to wait, and too, as stations for loading and unloading freight. Columbia’s first depot had been constructed in 1859, and during the Civil War, which erupted shortly after its completion, thousands of troops on both sides traveled through the depot with the eventual result that the city required the railroad line to put in a privy. After the war the number of passengers grew, and in 1875, the police department had to station two officers at the depot to meet each train after dark, because so many passengers were being robbed after disembarking the train.

In 1877, a second depot was built further west on the tracks. This depot was a union depot, meaning that several different railway companies used the depot. This depot remained in use as a freight station until 1960, when it was torn down. After the 1902 depot was completed, it became the main passenger station.

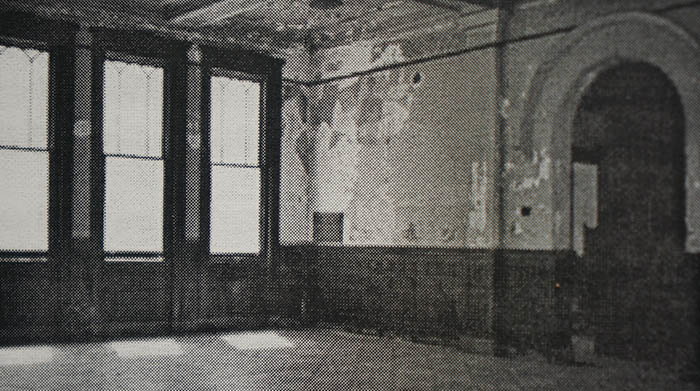

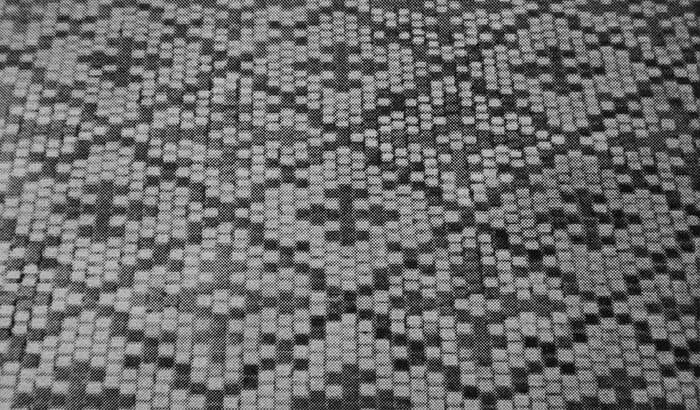

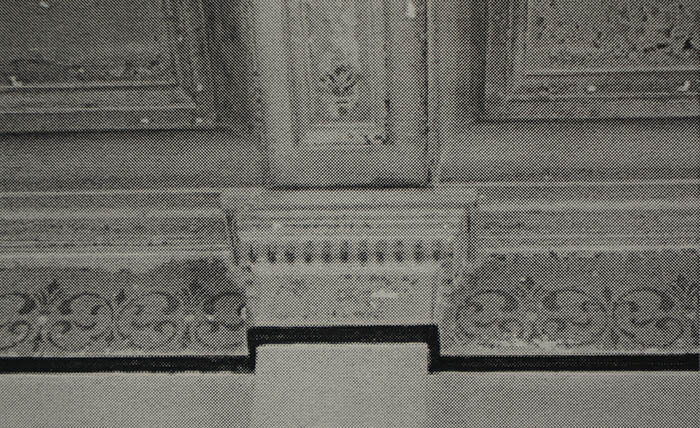

As trains pulled up to the third and present depot, passengers would have seen a three-storied stone building with one-storied wings on each end of the building Entering the backside of the depot, away from the street, a grand sight would have greeted them. The floor was colorful mosaic tile. The walls were painted from the ceiling to the chair rail, and covered with oak wainscoting below the chair rail to the marble baseboard. Positioned around the room were pilasters with molded capitals, and dentil trim. The paneled ceiling was decorated with plaster rosettes. If the passenger was waiting to catch another train, he or she could check the current time by glancing at the clock on the wall next to the ticket booth. This ticket booth was to the right in the main lobby as the passenger entered. A board with the latest postings was to the right of the ticket booth.

Pilaster with capital dentil trim, and beaming ceiling.

Passengers seeking refreshment did not have to leave the depot to obtain drink or food. A doorway to their left led into another room where local venders would come to sell food. Also, the women would find a restroom here. If passengers were in the middle of their snack and their train arrived, they could gain quick access to the tracks through doors that opened directly onto the tracks from this room.

Being built during the era of “Jim Crow” segregation, the depot had a separate waiting room for “Negroes” which did not have direct access to the main lobby. Decoration in the “Negro” waiting room was not as elaborate as in the other parts of the stations, but still featured decorative mosaic tiles on the floor with a Greek key border and marble baseboard. (Fig. 17 & 18) Black passengers could reach the tracks and the street directly from this room.

To pick up their baggage or freight, or make a complaint, passengers entered the wing to their left as they were exiting the train.

On the second floor, the stationmaster and his family had apartments, and there was also room for crews of the last train in for the day to sleep, since they would very likely be leaving early the next morning. Unclaimed baggage was stored on the third floor.

Passengers leaving the train at Columbia could, after gathering their belongings, leave the depot through the main lobby front doors, walk down a couple of stone steps, and arrive on the street, only one block from South Main Street. The courthouse was just five blocks to the northeast, and if the passenger needed a hotel, the Bethel Hotel had two omnibuses prompt in their meeting of all trains. The Bethel was a three storied hotel with modern fixtures, which its boasters claimed had “few superiors in this State.”

The railroad, with its impressive new depot, was an important emblem of the economic growth of Columbia and Maury County. The region had been growing since the mid-nineteenth century. Columbia, in 1850, was the third largest city in the state behind Nashville and Memphis. With mills and lumber companies operating in the area, Columbia was eager for a way to ship out its products. In 1888, when phosphate was discovered in Maury County the need became even greater as phosphate mining became one of the leading industries in the area. But the railroad and its new depot were also part of a larger movement sweeping the country in the late nineteenth century as the Progressive Movement spread beyond the big cities and into smaller towns and cities.

The railroad, with its impressive new depot, was an important emblem of the economic growth of Columbia and Maury County.

From 1890-1914, the Progressive Movement swept the country. Jane Addams and her Hull House experiment in Chicago were prominent during this time. The Progressives believed that people could improve their cities through careful planning. City planners began to advocate correcting the often-ugly blight of modern cities by allowing a bit of ruralization to come to the city. Good planning of a city would promote civic pride, allowing for “the full enjoyment of its theaters, museums, libraries, lectures, and social pleasures.” “Access to them should be rendered not only easy, and free from danger or discomfort, but attractive and elegant. ” At this time of city beautification, Columbia’s second depot was becoming run down. The push for a new and better depot can be seen as a result of the growing trend around the country for cities to improve their image and boost their pride in themselves. The right impression had to be made, and since the depot was the first building seen by many travelers to the community, it needed to be refined and elegant. This was achieved with the Romanesque architecture, stone exterior, elaborately tiled floors, oak wainscoting, and paneled ceilings.

However, the racial prejudice of the Progressive era was evident in the depot design. In 1896, in Plessy vs. Ferguson, the Supreme Court ruled that public facilities must provide separate but equal facilities for blacks. Thus, the depot was built with a separate “Negro” waiting room.

In 1916, the railroads reached an all-time high in rail mileage with 254,000 mile of line in service, but this was the end of “the golden age of railroading.” At the time when railroad companies were coming under more regulation by the Interstate Commerce Commission, new competitive transport facilities were coming on the scene. The Interstate Commerce Commission kept the railroads from becoming competitive with buses, airlines, trucking, companies, and automobiles. The number of passengers using the railroads began to drop off, and railroad companies began to decrease services. The reduction of passenger trains began in 1914 in Columbia, as two through trains were moved by L & N to another line. Ironically, the new depot had been built to provide “ample accommodations” for a business on the decline a little over a decade later. Through the early 1920’s, the trains held their own until the onslaught of car and bus transportation, but in 1927, the first local train was suspended. During the Depression and World War 11, due to gasoline and tire rationing, passenger train travel picked up. After the war, however, the decline started again so that in December of 1954, four trains were cancelled, leaving only two regular routes in operation for the next twelve years. In December 1966, the last two passenger trains, the No. 1 and No.4, were pulled from their routes and with their leaving, passenger service through Columbia ended.

In December of 1982, Seaboard Coastal Line took over control of L & N, and eventually tried to sell the depot. In 1986, J. A “Buddy” Morgan purchased the depot, and hired restorer Fred Karmie to restore the depot. Too little came of this effort because today the depot stands empty, seemingly abandoned, yet a prominent reminder of a past about which many people today have little knowledge.The station continued to be used as a local office of L & N for just over a decade, since freight was still being carried in-and-out of the area, but in the early 1980’s L & N closed the depot and moved its operations to Mount Pleasant.

It is a part of the history of our town. Its historical significance has been recognized, and it is on the National Registry…

The depot has been standing empty for years. When I walked in the first time, I was amazed at the splendor of the place, and saddened that so few people know anymore what it looks like, especially inside. Why does it have to be this way? People should know about this place. It is a part of the history of our town. Its historical significance has been recognized, and it is on the National Registry, but I would like to see it opened up again and made useful again. A first step in achieving this may be to open the depot during our local historical tours. This would educate the public and perhaps stimulate interest in using the building. Many towns use their old depots as local museums, and this would be perfect for this site. I also have envisioned it as a cafe where people can come for a cup of coffee and chat with friends, or to bring clients as they work out business deals, or just to show them part of Columbia, and how its residents appreciate their community, its past and its future.

1950s-1990s

aBOUt

HillHistoricProperties.com exists to showcase the rich architecture and history in Columbia, Tennessee through highlighting properties owned by David and Debra Hill. Each property has gone through extensive preservation and restoration to become timeless landmarks of the community. Mr. and Mrs. Hill were presented with the Association of the Preservation of Tennessee Antiques (APTA) Virginia Alexander Volunteer of the Year Award in 2019 for their historic preservation efforts in Maury County.